Evaluating Vintage Saxophones

by Paul D. Race

I love vintage saxophones that have been lovingly restored to playability, if not to their original patina. Nearly all American, European, and even Japanese saxophones made before 1980 are more solid than the average saxophone coming out of China today. What’s more, almost all 1914-1963 vintage horns could be restored to playability, if all the pieces are still there and they haven’t suffered catastropohic damage. Frankly they made things better in those days.

As a saxophone player who knows something about playing, teaching, and maintaining saxophones, I would rather see a child start out on a properly restored quality vintage horn than the $200-500 “instructor-approved” junk coming out of China today.

Think about this - before 1975 all saxophone players “cut their teeth” on saxes that were based on pre-1920 designs. And many surviving recordings of swing, jazz, rock, and even orchestral saxophones recorded before 1960 were made with those same horns.

That said, you probably don’t have any business buying a vintage saxophone (roughly 1915-1975) unless you already play saxophone and have some idea what you’re getting into.

If you want to learn saxophone and you don’t want to buy a new one (I don’t blame you), consider looking at “modern” saxophones, which started being made in the mid-1970s, and many of which can be made playable without a herculean effort. To start there, please jump to our Evaluating Used Saxophones article.

If you’re looking for a used C Melody, you may find this article helpful, since most C Melodies - even those being made today - are based on early-20th-century designs. You’ll also find our article Shopping for C Melody Saxes helpful.

Occasionally I run into someone who doesn’t play saxophone and wants to learn but thinks it would be cool to learn on a vintage horn. That’s right up there with the old joke about the guy trying to break into the movies in Hoboken, Pennsylvania. When asked why he doesn’t go to Hollywood instead, he says, “I don’t want to do it the easy way.”

Learning to play saxophone is one thing. Acquiring a vintage sax is another. They don’t actually go together as well as you might think.

Why does “Vintage” start with 1915 and end with 1975?

Admittedly, those dates are a little arbitrary. For some brands “Vintage” starts as early as 1914 or as late as 1918. For others it ends as late as 1978, but it’s a good rule of thumb.

Although many saxophones were sold before 1915, many of those are pitched higher than modern instruments, so it’s very difficult to play even the best ones in tune with modern pianos, orchestras, or bands.

By 1918, most saxophone manufacturers had gone exclusively to “Low Pitch” horns (Conn started in 1914). Those horns are compatible with modern bands, orchestras, and pianos. Since there were still “High Pitch” horns around - even on store shelves - for the first few decades, companies stamped either the words “Low Pitch” or the letter L near the serial number.

Also, because the horns needed to be reengineered anyway, many lines also offered other improvements, such as larger bores to provide a richer or fuller sound. Today there’s really no reason to own a “High Pitch” horn except as a collectible or maybe as a lamp stand. That’s why we have a “beginning” date range for our definition of “Vintage,” although you could, technically find saxophones dated much earlier.

“Low Pitch” Horns Worth Considering

Buescher’s “True-Tone” saxes and Conn’s New Wonder saxes are examples of these early reengineered horns. In fact, those designs were so successful that student-line saxophones based on them continued to be made long after newer designs appeared to serve the professional market. Buescher went on to develop the Aristocrat and the 400. Conn went on to develop the New Wonder II (with the “nail file” G# key) and the 10M-30M (the “Naked Lady”) series. All things being equal, the later Conn and Buescher horns are more desirable than the early ones. But don’t be fooled into paying $2000 for a New Wonder II (sometimes called a “Chu Berry”) when you could get a New Wonder in equivalent condition for $500.

Most of the earliest horns were silverplated. Beginning in the 1930s, lacquered sax became more common. By 1950, nearly every sax made was lacquered. In some cases, like the Buescher Aristocrat, both silver (pre-war) and lacquered (post-war) versions were made. In other cases, like the prewar Buescher True-Tone and postwar Elkhart, the horn was modified and repositioned as a student model when it went from silver to a lacquered version.

(Due to the popularity of relacquering horns in the 1950s and 1960s, don’t assume that lacquer established the age of the horn, though.)

Martin and King also made nice horns from about 1918 on (although they “petered out” eventually after World War II).

There were a few cheap horns that aren’t worth the time it would take to blow the dust off, but many of the “off-brand horns” were actually made by the name-brand companies as well. These were called “stencils.” Our article What is a Stencil Saxophone? provides more information on these horns and the companies that made them. Our article Stencil Saxophone List provides a list of reported stencil brand names and the factories that may have made them.

Attack of the Clones: Pro Features Filter Down to Student Horns

That doesn’t mean that saxophone engineering was at a standstill between 1915 and 1975 - professional models such as the Selmer Balanced Action continued to evolve. But most of those improvements did not find their way to student-line horns, and thus to the “mainstream” until the mid-1970s.

In 1967, Yamaha introduced a new line of “student” saxes that offered many improvements over contemporary US-made student horns. Ironically, some of those improvement included ergonomic (playability) features that Selmer Paris’ professional horns had adopted decades earlier, but which US manufacturers of student saxes had never considered adopting. Yamaha’s share of the student sax market grew rapidly. In response, Selmer US quickly scrambled to reengineer their student line horns to include the same features, and the Bundy II was built. For a discussion of the kinds of ergonomic improvements that were made before and during this revolution in the industry, please see our article on “Saxophone Ergonomics.”

Soon, all major saxophone manufacturers standardized on Selmer Paris-inspired designs. Unfortunately the factors that had heretofore differentiated distinctive topline horns like the Conn 10M and 30M, the King Super 20, the Buffet Super Dynaction, and the Buescher 400 (actually discontinued in the 1960s) disappeared.

From about 1980 on, all major saxophone brands have been largely copies of the Selmer Mark VI, the horn that Yamaha copied most closely. Some have been very good copies. Some have been very bad copies. But the market became so glutted with homogenous offerings that the only way most companies could compete was to move manufacturing to Asia and compete on price. Some companies survived in name only - the current Asian offerings with their brands stamped on the bell have no real relationship to the century-old history of the brand itself. That’s why our definition of “Vintage” only goes up to the mid-1970s.

How can I claim that most forty-year-old instruments you see today are not, technically, “vintage” horns? Because most horns made between 1980 and 2014 are nearly interchangeable except for quality control and subtle engineering differences.

Some folks will tell you that this means that horns made before 1980 are too hard for kids to start on, or that if a kid starts on a 1950s-era horn he or she will have trouble adjusting to a modern horn later. But this is a marketing lie. Saxophone note fingerings haven’t changed since about 1905. Only the shape and relative position of certain keys has changed. Players who have learned on the old designs have no problem adjusting to the new, and adults have no problem going the other way. That said, for smaller kids, the new ergonomics may make modern saxophones easier to play. And, all things being equal, many adult players prefer the new way as well. If you’re interested in seeing more information about these ergonomic changes that caused the “great divide” between “vintage” and “modern” saxophones, please see our article Saxophone Ergonomics.

In fact, many people would push the definition “vintage” back a little farther. To many folks, a “vintage” horn isn’t worth collecting unless it was made before World War II. (Notable exceptions would include Selmer Balanced Action and Mark VI horns and Buescher Aristocrat and 400.) It is true that postwar student horns are nowhere nearly as “collectible” as the prewar models they were based on - for one thing, they glutted the market, and many were grossly abused.. But for our purposes, we’ll set the dividing line for each model to the point where the ergonomics changed. And that varied from model to model.

Your Assignment, Should You Decide to Accept It:

So most vintage sax hunters look for one or more of the following:

- A “Low Pitch” prewar name-brand sax (most likely a Conn, Buescher, Martin, King)

- A “Low Pitch prewar “Stencil” made by Conn, Buescher, Martin, or King. Respectable stencils include Lyon and Healy (mostly made by Buescher), Indiana (made by Martin), Pan-American (made by Conn), etc. Stencils don’t always have the same features, but they’re usually solid. See more about Stencils in our article on the subject.

- A 1946 - 1975 improved model sax (including French Selmers, Buescher 400, Buescher Aristocrat, and Selmer Signet - there are more but these are the ones I’m most familiar with )

We also will assume that you’re not necessarily looking for 1946-1975 student horns. True, horns like like the Selmer Bundy used much of the same engineering that the “professional horns” of the 1920s-1940s used. Restored, and fitted with a professional mouthpiece they have a lot to offer. But they glutted the market, and most of them got “beat to death” by their student owners. Today, they have a largely undeserved reputation as a “throwaway horn.” If you come across one cheap and it can be made playable without a huge investment, have fun with it. Just don’t assume you’re recoup your investment if you ever try to sell it.

Regarding restoration, some horns need more restoration than others. And some folks who claim to do restoration do a better job than others (see below). Moreover, the costs and outcomes vary wildly. Unless you know exactly what you’re doing, you might wind up with a $200 “project horn” that will take $800 worth of work to turn into a $500 horn.

This is where having a real sax player on your side is critical. And learning to tell the truth from urban legends and wishful thinking when you scan the Internet looking for more information about a “too-good-to-be-true” deal.

Note: The advice on this page also depends on you having access to an honest woodwind repair person. Technically almost every woodwind repair person I’ve ever met has been honest. But the stores they work for aren’t always honest. For example, the biggest music store in my area won’t let you talk directly to their repair people. Instead, they’ll try to talk you into a new horn, and if they can’t do that, they’ll charge you double for the repair just because by now you’re a “captive audience.” Ask your woodwind-playing friends who they use - the name of the repair person, not just the name of the store. Often mom-and-pop stores run by instrument repair people will be the most helpful and honest.

Also, if you’re interested in a vintage pro horn, or if you come across one and wonder if it’s a better deal than the student horns you’re looking at, there are some good recommendations and “gotchas” on the Saxophone.org Saxophone Buyer’s Guide page.

The Hunt

If you live in a metropolitan area, Craig’s List may give you a line on several horns. Don’t assume that:

- Any of the information in the ad is correct,

- Any of the sellers are honest, or

- Any of the prices listed represent the true value of the horn.

Pay the most attention to ads with good photos and specific information. Call people who have phone numbers, e-mail or text those who don’t and ask for their numbers and a good time to call. When you’re on the phone, ask about the horn’s history. Get the serial number of you can, that will help you assign a date.

If you’re tempted by an online ad, look for one with lots and lots and lots of in-focus photos. If this guy seems like a reseller (most eBay sellers are), look at the seller’s other stuff and see if he seems to sell a lot of saxophones - if it’s a bass guitar player who picked up a sax in trade, he may be innocently ignorant of problems with the horn or cluelessly passing on fake history information that he was given. Also, a 100% positive feedback rating from a fellow who usually sells Hummel statues may not indicate that this guy is really ready to give you the information you need to make the right decision.

Looking It Over

Let’s assume that you’ve used Craig’s List and found a local horn or three that might suit your needs. Or you have a heavily-photographed, believably documented, reasonably priced possibility on eBay. Here are some things to look for:

Finish Issues

Experts and professional sax players looking for vintage horns aren’t usually “put off” by a less-than optimum finish, but it’s worth knowing the most popular kinds of finish and whether damage is cosmetic or worse.

Silverplate finishes are the most common on pre-1934 horns, and occur on several until the late 1930s. Most horns have a satin finish on the body and a shiny finish on the keys and bell. If you see a horn that was obviously meant to be shiny all over, it might have been a “step-up model. Don’t be surprised to see places where the horn is darkened or black from tarnish or where the silver is worn off of the keys and the brass shows through. Most tarnish can be removed with a good silver polish and a little elbowgrease. (BTW, third-rate “restorers” often use something like an electric screwdriver with a buffing pad try to buff some shine “back” into the satin finish, which results in wearing off some - or occasionally all - of the finish.) If any “wear-through” seems to have come from rubbing, that’s just a sign of normal handling. In fact, some players don’t mind having a horn that was originally silverplated and now is worn almost completely down to the brass, as long as it’s from normal handling and not from abuse.

By the way, most silverplate horns have a very thin hint of gold inside the bell, called a “gold wash.” Some even have a gold wash over the part of the bell where the engraving was done. If your horn doesn’t have it, that’s fine, just wanted to point out that some advertisers will take photos of that and claim the sax is “gold-plated,” which it isn’t.

Advertisers like to claim 95% original finish or some such, which is technically impossible to calculate. There is also a tendency to price a horn that’s “98% original finish” higher than one that’s “85% original finish.” Not only might the “85%” horn be in better shape overall, it might actually have more of the original finish than the “95%” horn, just a more honest advertiser. This is one place where having hands on is important. And or clear photos from every conceivable angle.

That said, if a lot of the silverplate seems to be scratched off or if there is green corrosion anywhere, the horn may have suffered rough handling beyond the “normal wear and tear,” and it may be a warning sign that other, harder to see, damage is present.

Gold plate is extremely rare. It was usually reserved for top-of-the-line horns, although it might be worth keeping in mind that there weren’t as many differences between top-of-the-line horns and “run-of-the-mill” name brand horns in those days as there is now. Usually better quality control and a couple more keys were the main difference. Most horns that were originally gold-plated have lost much of the gold. Not a problem unless the horn shows signs of damage. Obviously, anyone selling a gold-plated horn that has most of its original finish will charge more, but that doesn’t necessarily mean the horn will play better.

Ironically, ignorant or deliberately misleading sellers will often describe a lacquered horn as “gold-plated” because of its color.

Lacquer finishes started becoming common in the 1930s and were pretty much universal in post-war horns. Lacquer was cheaper to put on and didn’t tarnish. So a lacquer horn that was handled carefully was very low maintenance. However the lacquer finish could scratch and let moisture through, which WOULD cause the brass to corrode. That’s why so many 1950s and 1960s student horns have more green than “gold” in their coloring - they were used by careless students, and may have gone through marching band, been scratched up and put up moist night after night.

Sometimes folks try to refurbish valuable lacquered horns by removing the damaged lacquer, polishing the brass smooth again, and relacquering the horn. But in most cases, the new lacquer is not to factory specs, to put it nicely. That’s one reason some collectors and pros are satisfied to use a horn with most of its original finish missing.

Lacquered Horns that Started out Silverplate - In the 1940s and 1950s it was common for “refurbishers” to strip the remaining silverplate from a sax and lacquer it. That didn’t help the sound, but silverplated saxes had gone out of style, and a lot of folks wanted their saxes to look shiny and new.

It still happens, in fact. In some cases, families whose kids want to learn sax decide to fix up Grandpa’s horn so it looks like all the new ones. As long as the rest of restoration is done properly, this doesn’t hurt the kids’ chances of learning sax on the horn, but it’s a lot of money for no real benefit. As an example, I own a 1920s Selmer New York (Buesher stencil) to which this happened within the last few years.

Does Relacquering Matter? To some folks, relacquering a vintage horn diminishes its value, because it supposedly changes the tone of the horn. Of course, that’s never been proven scientifically, and the tone of the horn changes a lot more when you change mouthpieces, or even reeds, so I’m not sure that’s a reason to automatically prefer a battered old original finish to a well-done relacquer. To me, the bigger issues relacquering could present for vintage horn buyers are that:

- Relacquering disguises the age of the horn, especially of stencils (like my Selmer New York) that have no definitive serial number record. Recently, I saw a relacquered 1920s stencil being advertised as a 1980s horn. More commonly, 1920s horns are listed as 1940s or 1950s horns based simply on the fact that most horns were lacquered by that time. Again, if the horn is solid, that’s not a problem, but if the vendor is lying or ignorant about that, he or she may be lying or ignorant about something else, as well.

- Relacquering may hide abuse. If you’re examining a horn you believe is relacquered, look for places where the lacquer is uneven - it may be hiding soldering repairs or other signs of abuse.

Most relacquering is obvious if you get your hands on the horn. For one thing, the etching will have softer edges and obscured details. Uneven coverage is another clue. If you’re uncertain whether a horn is relacquered, and it will affect your purchasing decision, check out “Dr. Rick’s” Relacquered Saxophone Page.

For another opinion on the subject, check out ThisOldHorn.com’s article “Original Lacquer?”

Obvious Damage

Now I’ll be honest, a saxophone can be pretty banged up and still play well. But signs of careless handling or apparent abuse might indicated hidden problems as well.

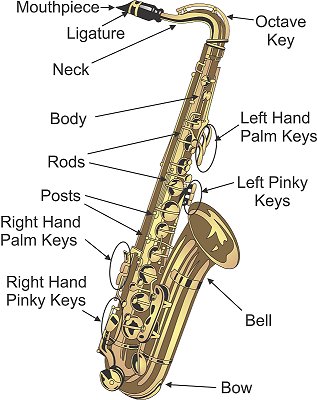

The bell is the part that most folks think the sound comes out of. It’s shaped like the opening of a cornucopia. If the bell is bent out of shape in any way, you should probably write the horn off period. Yes, it can be fixed, for a price, but it is almost impossible to damage the bell of a saxophone with normal handling.

The bow is the U-shaped part that connects the bell to the body. The most common ding on saxophones is a dent from banging the bow into something (or maybe dropping the horn on the bow). Professional horns have a guard that protects the bow. Student horns generally have some reinforcement that may not quite do the job. But a slightly dinged bow is so common that a lot of folks wouldn’t even notice the difference in sound. I’d say if the ding is less than the size of a 50-cent piece and no deeper than, say 1/8”, and the brass is not punched through or significantly creased, I wouldn’t worry about it too much. If there are a lot of dings on the bow, it was probably a school-owned horn and has probably been abused in other ways. If any of the dings looks like it would alter the flow of air through the tube (say it’s very broad or deep or both), assume that the horn has been dropped hard enough to distort the body and knock things out of alignment.

Up at the other end, the neck is the part that connects the mouthpiece to the body of the horn. It will have a loop-shaped lever with a pad on one end - that’s the octave key. The cork on the neck should not have big holes - this is an inexpensive fix but indicates that other things might need fixed as well. A few scratches on the neck don’t hurt anything unless you promised your kid a new-looking horn. But if the pad on the octave key doesn’t sit squarely over the tone hole so that it has a optimum seal, and you can’t make it fit squarely over the tone hole by adjusting it with a little pressure, something’s wrong. A bigger problem is if you see any sign that the the neck has ever been bent at all, such as bulging or cracks in the lacquer. Run - do not walk - away. Also look for signs that the part that goes down into the saxophone has ever been resoldered to the neck - that may be a sign of an innocent accident or a symptom of a pattern of abuse.

The keys are levers that make the pads open or shut on the horn. About eight of them have mother-of-pearl-ish buttons (called “pearls”) that are glued right to the metal over the pad. The rest are connected to the pads by long levers and sometimes by a series of levers. Look the horn over and make certain nothing seems to be missing. Everywhere there is a post (the chess-pawn shaped supports), there should be something attached to it, a key or a rod or something. A “freestanding” post means that the horn is missing something that will cost real money to replace. Operate each key, even if you don’t know which fingers go where. The motion should be smooth and precise, not sloppy or sluggish.

By the way, if a pearl or two are missing, that’s an inexpensive fix, but it might indicate a pattern of abuse.

Wear patterns on the keys that are not buttons do not disqualify the horn. For example, there are several lever-shaped keys that are arranged to so a player can hit them with the palm of his or her hand. At least one of the palm keys in each cluster will show significant wear if the horn’s been played at all.

Below the normal right and left hand position are other keys that the player is supposed to hit with his pinky. Again, at least one or two of the pinky keys in each set will show significant wear if the horn’s been played at all.

If there’s noticeable wear on all the palm or pinky keys, you’re looking at a horn that has been played much longer. As long as it’s been taken care of, that’s not a problem.

The posts are the pieces that support the keys and the rods. They are shaped like tiny stanchions or chess-piece pawns. Look at the posts, especially those that are most exposed, for signs that:

- The post has been broken off and resoldered back on.

- The post has been bent

- The post has been knocked askew in such a way that has bent the body of the horn underneath it.

All three cases could be a sign of abuse, especially if the horn has other problems. However, the first case could be a symptom of an isolated accident. If the resoldering job looks professional, chances are it was done by a repair person who made certain everything was fixed when he or she did the work. The second case means that the horn needs real work. The third case may mean that the horn is irreparable. In any case, damage to any post drops the resale value of the horn considerably, and makes a lie out of any “like new” claim.

The rods are the long tube-looking things that connect some of the key to pads that are several inches away. There should be no noticeable wear on the rods unless the horn was constantly mishandled. Sight down the horn like you would an arrow. If the longer, more exposed rods bow in a little that means that the horn has been carried the wrong way extensively, and there might be other evidence of careless handling. Neither problem makes the horn a write-off in and of itself, especially if the keys and pads attached to the rod still seem to be doing their jobs smoothly and precisely. The one rod problem that disqualifies a horn automatically is any sign that a rod or rods have been knocked out of shape and “re-straightened,” or that a whole assembly has been knocked askew.

Under many of the rods are springs, little steel rods or pins that hold the pads in their default position when you’re not playing the key. If you push one of the lever- or rod-attached keys and nothing happens, it could be because a spring is broken off or missing altogether. Again, this is a minor repair, but if the seller swears he was playing the thing just yesterday, don’t believe anything else he says either. By the way, accomplished sax players all know how to temporarily “fix” missing springs by wrapping rubber bands around the horns. Don’t laugh - rubber bands have gotten a lot of pros through the rest of their gig but they shouldn’t be left on once the gig is over. If you see an unusual corrosion pattern running across the rods or the body, that may indicate that someone “fixed” a missing spring with a rubber band and left it on for months - another sign of neglect.

In one end of each rod is a set screw. If any of these are missing, the rods don’t stay on the horn, so chances are they’re all there, unless you notice that a screw has come out and been replaced by a sucker stick or something.

The pads are the little leather disks that seal off the holes of the horn. The original pads of most saxes made before 1930 (and many after) tend to be white. It’s possible to buy white pads today, but if you see a vintage sax with white pads being advertised as “restored” or “needs minor work to be made playable,” be very suspicious. The cost of a repad varies from one area to another, but it’s never cheap. On the other hand, if a vintage horn has brown pads, it has probably been repadded at some point in the past. If most of the pads are soft, you may only need to replace the top three or four, which is much cheaper.

If many of the pads are sticky, that means the player drank a lot of Coke while playing the horn, and it might need a good internal cleaning. Each pad should fit firmly over the tone hole in exactly the circular pattern that you can see indented in the pad. That indent was put there when the horn was assembled. If any of the pads don’t sit firmly on the indent, or have two circular indents, that key has been knocked out of alignment, which could be a sign of bigger problems.

Note About Pro or Classic Horns

Please note that if you’re looking a horn that started out as a pro horn like a Selmer Balanced Action, or if you’re looking to restore a classic horn with historical value, like a Buescher 400 or Conn New Wonder II (“Chu Berry”) or 10M, 26m, or 30M (“Naked Lady”), nothing on this list should dissuade you - just remember that if the horn is structurally sound (no missing pieces, no twists in the body, straight rods, no broken or bent posts, no dents that infringe on the airflow), you may still be looking at $300 or so to get it into top playing condition. If there is structural damage, or if you want to repair damaged silver plating,, you may be adding $600-1000. That said, If you come across a Conn Naked Lady or a Selmer Super Balanced Action basket case for $400, and it’s going to cost you $1200 to get it restored to optimum playing condition, it might well be worth it. On the other hand if someone’s selling a non-restored New Wonder II for $1000 and it’s going to cost you another $800 to fix it up, move along.

Summary of What to Look For

Once again without all of the explanation, here’s a list of thing you should consider warning signs evaluating vintage horns.

Finally here are signs that could indicate abuse, dropping, and/or improper storage (such as a hot attic). Only a few will disqualify a horn by themselves, but more than a couple of these on the same horn means that it was seriously mishandled and may have problems you can’t see.

- The bell is bent out of shape (I’d skip a student horn just on this account).

- Many dings on the bow including some that are deeper than 1/4”.

- Several missing pearls

- Rods have been bent out of shape (even if they’ve been bent back)

- Posts that have been knocked off and resoldered or that have been bent (especially if they distorted the body shape)

- Any sign that the neck has been bent.

- Horizontal stripes of discoloration or corrosion on the rods - evidence of rubber bands left too long on a horn after a spring failure.

- Evidence of resoldering anywhere on the horn.

- Lacquering over a horn that was originally silverplated.

Again, these issues wouldn’t necessarily dissuade anyone who was shopping for a pro or classic horn, but if you’re just looking for a vintage horn to play, don’t buy trouble.

Unrestored Vintage Saxophone Values

While it’s impossible to predict prices around the country, a top-of-the-line, unrestored but restorable vintage sax might be worth up to $300, with the most desirable models (Conn 10M and 30M, King Super 20, Buescher 400, etc.) demanding a little more. But you have to assume that you’ll be putting $400-600 into additional work (more if you are worried about cosmetics). The good news is that for less than $1200 you’ll have a classic horn that will outperform and outlast any $2000 (list) horn you can buy today.

If an unrestored but restorable horn is a stencil of a name brand, you might be looking at the $100-150 range. Stencils may lack features of their name-brand counterparts. It’s also worth noting, that stencils tend to be based on 1915-1920s engineering so you won’t see a stencil of the later, more desirable vintage horns. But the “real” stencils were made on the same lines as the name brand horns, and are generally just as durable.

On the other hand, you sometimes see a true no-name piece of junk being advertised as a Conn or Buescher stencil. So examine photos carefully, and compare every detail to photos of the “name brand horn.” Yes, there may be fewer trill keys, or the bracing under the neck or on the bell may be less elaborate, but the basic mechanics of the horn will be just the same.

Notes About the “Value” of Various “Restorations”

When you start shopping for vintage saxophones, you’ll soon see so-called “restored” horns. Some of them really are restored to play as good as new (or better,even). Some are just cleaned up so they look good in photos. As you can probably tell from my discussions above, there are different kinds of “restoration”:

- Online Auction “Gotcha” Restoration - Polishing it up so it looks good on eBay. Claiming that you don’t play sax yourself but you’re pretty sure it will take only minor tweaks to make playable. Disallowing returns.

- Bare Minimum - Doing the minimum necessary to get sound out of it, which might include replacing a pad or two. Claiming that you don’t play sax yourself but you’re pretty sure it will take only minor tweaks to make play like a classic horn. Disallowing returns.

- Sort-Of Restoration - Cleaning it somewhat and replacing any bad or borderline pads or springs with materials that work, so that the average saxophone player can, technically PLAY it. Disallowing returns. These guys will add $200 or more to the cost of the horn but the real work is yet to be done.

- Repad Only - Putting in new pads and replacing any missing or failing springs, not necessarily with the same quality materials, though. Some cleanup, moderate testing. Expectation is that you or your woodwind guy can do any further tweaking required. Returns usually allowed. These guys will usually add $300 or more to the cost of the horn, which would be worth it if they used premium materials and really brought the horn up to optimum playability. But they usually don’t.

- All-But Finish Restoration - Disassembling it so you can give it a thorough cleaning, polishing the remaining finish with appropriate materials, replacing the pads and springs with materials that are at least as good as the original if not better, followed by extensive testing. This could easily add $400-600 to the value of the horn, but it’s a legitimate expense, since everything they do goes to improve the tone and playability of the horn.

- Repad and Lacquering or Relacquering - Sometimes you’ll come across an instrument on which the horn has been relacquered, Usually the pads are replaced as well. These tend to be advertised as “like-new condition.” but the “restoration” is really more for visual appeal than musical improvement. In fact lacquering a once-silverplated horn or stripping and relacquering a lacquered horn nearly always reduces the thing’s volume and tone - relacquering never reproduces the original coating which the factories used. These guys will also add $600 or more to the cost of the horn, but since the cosmetic “upgrades” may do more harm than good, I wouldn’t consider this a “restored horn” in any meaningful sense.

- Total, Authentic Restoration - This really applies to silver- or gold-plated horns, since relacquering is usually a bad idea. A handful of people do everything in the “all-but-finish” restoration, but they also bring out the maximum appearance of any plating that remains and replate parts where it has worn off. They even re-engrave any engraving that was affected by the replating. When they’re done, the horn looks and plays like new or better. Depending on the amount of plating involved, the cost could be up to $2000. So this tends to get done only on classic horns that will be worth $3K or more once they’re finished.

One of the points of the list above is that, unless you know what you’re doing and get your hands on the horn, you really don’t know what the vendor means by “restored.” For most vintage-horn hunters the kind of restoration we called “All But Finish” is the most appropriate.

But if you shop long enough, you’ll see some actual restorations as well s false claims. Which is one reason shopping a while before you take the plunge might be a good idea. Just don’t keep shopping until you own “one of each.”

Other Resources

Felix’s Saxophone Corner Blog has a nice two-page overview of the major brands that made desirable vintage horns. Click here to jump to the first page of the article.

Saxophone.org’s Saxophone Buyer’s Guide page has some good tips, especially if you’re looking for a pro or classic horn.

Other articles you may find helpful include:

Another resource, the Horns in My Life articles describe various saxophones (and one flute) with which I’ve made a personal connection over the last 45 years. Some folks who’ve had similar horns will find it a helpful resource. Others will just like to reminisce along with me. On the other hand, if you come across one of these horns while you’re shopping for a saxophone and want to know more about it, you may find one or more of the articles helpful.

The list is in the sequence in which I owned the following horns, not in the sequence they were built, which is way different.

All material, illustrations, and content of this web site are copyrighted © 2011-2015 by Paul D. Race. All rights reserved.

For questions, comments, suggestions, trouble reports, etc. about this web page or its content, please contact us.

| Visit related pages and affiliated sites: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|