|

Scales & Melody

Note: This article is being archived, as parts of this web site are being rearranged, and redundant articles are being eliminated. To see the current version of this article, now hosted on the CreekDontRise.com page, please click this link.

This article describes the most basic kinds of scales you'll encounter in most forms of Western music, including popular music of all kinds. Chances are you know some or most of this - but we wanted to fill "in the gaps" for folks who may have missed something along the way.

What is a Scale?

One way musical tones can be differentiated is by pitch - that is, tones can sound "higher" or "lower" because something (a reed, a string, a bell, column of air in a tube, etc.) is vibrating either faster or slower.

To the human ear, the tone seems to "repeat itself," albeit at a "higher level," every time the pitch doubles. As the old song says, "that brings us back to Do". In Western music, we call that jump an octave. And most cultures with deep musical traditions recognize the octave.

Most cultures also recognize the note we call the "fifth," which is in the middle between notes that are an octave apart. Blame physics - nearly any vibrating item vibrates not only at the root frequency (the one you think you're hearing) but also at a frequency an octave above that, then a fifth above that, and so on. Those extra "embedded" notes are called "overtones" and they're the reason that harmony-oriented music from all cultures tends to have certain notes in common.

That said, some cultures recognize more of those notes than other cultures.

- Some cultures have recognized only five tones within the octave, what we call the pentatonic scale (described below).

- Modern Western cultures recognize 12 tones per octave (what we call the "chromatic scale").

- Some Eastern cultures where melody is "everything" and harmony is almost nonexistant, have recognized twenty-four or more notes per octave.

Most American music students are surprised to discover that European music used to have 18 tones per octave - before the 1600s, C# was a different note from Db. But you won't have to worry about that too much when you're learning modern music theory. In J.S. Bach' s Well-Tempered Keyboard (Clavier). Bach proved that you could produce listenable music if you divided the frequences within each octave twelve different ways. C# now equals Db (they used to be two different notes, believe it or not, and they still are different for classical violin players).

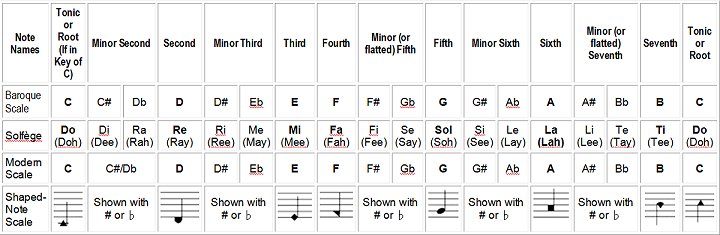

The following table shows the relationship between the Baroque (pre-Bach) scale and the modern (post-Bach) scale. Note: Classical violinists still use the Baroque scale, especially when playing melodies.

We've also included the "Do, Re, Me" ("solfège") spellings for each note, which were used, not only by classical singers, but also by "Sacred Harp" singers of the North American 19th century, as well as many other users of "Shaped Note" hymnals. (Go rent Cold Mountain if you want an example.) Note that a "Do" sharpened is a "Di," while a "Re" flatted is a "Ra," even though they're the same note on the piano. Like classical violinists, classical singers make a distinction between C# and Db, usually depending on what key the song is in, and in some cases on whether the melody is going up or down. Phonetic pronunciations are also given for the note names. Note that most Europeans pronounce "Do" as "Doo", but thanks, in part, to Rogers and Hammerstein, Americans usually say "Doh."

The notes of the C major scale, "proper," are shown in bold.

So now most Western music is based on a twelve-tone-per-octave scale, as represented by the black and white keys on modern piano keyboards. Our melodic and harmonic structure, though is built around the assumption that most tunes will tend to use only seven of those tones at any given time. If you want to stay on the "white keys," you'll find two typical scales on those keys.

Major Scale

Starting with C and going up to C, you get what is called a "major" scale. This is called a "major scale" in part because the two-whole steps between the first and third note on the scale produces a "major third."

|

Note Names (in a C Major Scale)

|

Tonic or Root (If in Key of C)

|

Second

|

Third

|

Fourth

|

Fifth

|

Sixth

|

Seventh

|

Tonic or Root

|

|

C

|

D

|

E

|

F

|

G

|

A

|

B

|

C

|

Minor Scales

If you keep avoiding the black keys, and you start with A and go up to A, you get something called a "minor" scale. The step and a half interval between the first and third note creates a "minor third," which has a distinctively different sound from the major third. Depending on how minor scales are used, they can sound haunting or harsh, and many things in between.

Because A minor uses exactly the same key signature as C major, A minor is called the "Relative Minor" of C. In other keys, D minor is the relative minor of F, because they both use one flat, and E minor is the relative minor of G because they both use one sharp.

Natural Minor Scale

|

Note Names (in a A Minor Scale)

|

Tonic or Root (If in Key of C)

|

Second

|

(minor) Third

|

Fourth

|

Fifth

|

(minor) Sixth

|

(minor or flatted) Seventh

|

Tonic or Root

|

|

A

|

B

|

C

|

D

|

E

|

F

|

G

|

A

|

The version above is called the "natural" minor scale because keeps exactly the same key signature as the relative major, C. But minor keys often "break the rules" a bit, especially when it comes to the seventh note of the scale, which, by key signature, should be a whole step (two half-steps) below the tonic.

Harmonic Minor Scale

But a song in the of A minor may incorporate an E major (or E7) chord instead of an E minor chord. This means that instead of a G, the song uses G# for the seventh note of the scale. Because this change in the scale is brought on by choices in harmonizing the tune, this kind of scale is called the Harmonic Minor.

Melodic Minor Scale

The "melodic minor" scale bumps up the the sixth and seventh note of the minor scale up when the melody is rising, then returns it to its natural setting when the melody is falling:

|

A

|

B

|

C

|

D

|

E

|

F#

|

G#

|

A

|

A

|

G

|

F

|

E

|

D

|

C

|

B

|

A

|

Pentatonic Scales

Ninety-nine percent of the melodies in modern music use one of the scales above. However a great many traditional melodies are influenced by a scale that was popular in folk music of the middle ages, and is still found today in traditional Celtic music and related forms.

A "pentatonic scale" uses five notes per octave only. If you've ever played a tune on JUST the black keys of a piano (say "Mary Had a Little Lamb," you've heard the most common pentatonic scale.

The following table shows this scale as started in the key of C:

You can also play pentatatonic songs in the key of F and G on just the white notes of a piano.

Example songs that use this pentatonic scale include:

- Many hymns from Shaped-Note and Sacred Harp traditions, such as "Be Thou My Vision," and "On that Earliest Easter Morning"

- Appalacian folk songs with Celtic roots such as "The Waggoner's Lad," and "I Went Down to the River to Pray" (as featured in the film Brother, Where Art Thou?)

- Many oriental tunes, such as Arirang, the unofficial national anthem of Korea

In addition, many American folk tunes (such as "Shennandoah" and "Tis the Gift") are based on the traditional pentatonic scale, even though they have added other notes (especially "Fa", which is ordinarily missing). Songs that seem to substitute a sixth where a seventh might be expected are a giveaway.

Modes

Mode is an old term that was invented when there were many more kinds of scales than there are now. Today any scale you can play on all white keys is technically a "mode." So if you play from C to C without playing any keys, you've played a mode (Ionian). If you play from A to A without playing any black keys, you've played another mode (Aoelian).

But wait, you might say, we already know those as the C major and A minor scale respectively. You would be right, of course. But what about a scale that goes from D to D without playing any black keys (Dorian mode). Frankly it sounds a little funny. So does the scale that goes from G to G without any black notes (Myxolodian mode). But both are common in certain kinds of ethnic music, and it pays to recognize them when they occur. In addition modes are widely used in Jazz, so if you have any leanings that way, you're just getting started.

The names of modern modes come from the work of ancient Greek mathemeticians, though our modes today are not related to the modes of the ancient Greeks. The following table shows the mode that would relate to each "scale" played only on the white keys.

|

Ionian

|

C to C

|

|

Dorian

|

D to D

|

|

Phrygian

|

E to E

|

|

Lydian

|

F to F

|

|

Mixolodian

|

G to G

|

|

Aeolian

|

A to A

|

|

Locrian

|

B to B

|

|

For an exercise, sit down at a piano and play each of these scales up and down. You'll notice that:

- Ionian, Lydian, and Mixolodian sound basically major

- Dorian, Phrygian, and Aeolian sound basically minor

- Locrian just sounds weird - the scale includes a diminished triad, the only one on the keyboard.

Ionian Mode:

Dorian Mode:

Phrygian Mode:

Lydian Mode:

Mixolodian Mode

Aeolian Mode

Locrian Mode:

It is no surprise that some of these modes are almost never used. But some folk songs use Dorian and Mixolodian, and some "classical" composers use them all.

In addition, Appalacian Dulcimer players, who only have seven frets per octaves (not 12) play songs in modes besides Ionian and Aeolian. If you ever try to get through The Ballad Book of John Jacob Niles, you'll see what I mean.

Relationship of "Mode" to Key - You may be used to thinking of a song that is in the key of C as having no sharps or flats. A song in A minor usually has no sharps or flats either, unless you're including accidentals for "harmonic minor" or "melodic minor." But with modes, the relationship betwen key signature and key may not be obvious. For example, what if your song seems to be in the key of G but there is no F# (as there usually would be)? It's possible that the arranger made a mistake. But it's also possible that the song is in Mixolodian mode.

Once again, modes besides Ionian and Aeolian are very seldom used in music today, so you'll probably get along just fine if you don't memorize the various mode names. But knowing that these different modes exist may help you survive a serious World or Jazz music encounter without looking TOO stupid.

Scales and Melody

In most modern music, including pop, rock, etc. the harmony changes, but the melody generally stays on the same scale throughout the tune. The most common exceptions include:

- Melodies that go between one minor scale and another

- Melodies that go between major and minor or vise versa ("Greensleeves/What Child is This?" and "We Three Kings" are good examples).

- Melodies in songs that have secondary dominants (see our discussion of chords for this variation, which temporararily seems to change the key of the song)

- Melodies in folk songs that might go back and forth between one mode an another

- Melodies in jazz, blues, or bluegrass that occasionally substitute flatted 3rds, 5ths, and 7ths.

Scales and Harmony

Most modern Western music uses various "chords" to accompany the melody. As an example, the "root" or "tonic" chord of a song includes the first, third, and fifth note of the scale. A C chord contains C, E, and G notes. As long as you have a melody that doesn't stray from those notes, your harmonization can keep playing a C chord all day long. But of course that gets a little boring.

|

C chord

|

C scale with notes that are in the C chord shown in blue

|

|

|

|

What happens when your melody decides to sit still for a bit on a note that ISN'T in the C chord, such as D, F, A, or B? You find a chord that contains that note. Due to rules of harmony that are explained elsewhere, a song in the key of C is more likely to use a G or G7 chord than any other chord except C. (That’s why it’s called the “dominant” chord.)

So if your melody sits for a bit on a D or B note, you would consider putting a G chord behind it. In fact, if one of your lines besides the last one ends on a G note, you might want to stick a G chord in there just for variety.

|

G chord

|

C scale with notes that are in the G chord shown in blue

|

|

|

|

As an example, most hymnbook arrangements of “Amazing Grace” put the song in G and harmonize the end of the second line on the G chord, which sounds very static and boring. The note on which you sing “me” is a D, which gives you the opportunity to go to a D or d7 chord, which is the way most Gospel, Southern Gospel, and praise bands sing it.

If your song decides to hold onto an F or A note, chances are you'll stick in a F chord. After all, next to G and C, F is the most common chord in a song in the key of C. That’s why it’s called the “subdominant” chord.

|

F chord

|

C scale with notes that are in the F chord shown in blue

|

|

|

|

No matter what chord you go to, most of your melody notes in most folk, pop, rock, and praise tunes will stay in the key of C. We’ll describe the most common exceptions when we address chords and harmony.

Scales and "Ad Libbing."

As crazy as this all sounds, once you learn how scales work and how most basic chords work (in our other articles), you've got ninety percent of the information you need to make up your own tunes, such as instrumental solos. Staying with C for simplicity's sake, and sticking with our three-chord pattern, which gets easier to hear the more you play and the more songs you learn:

- Assume that most of the notes of your solo will be in the C scale.

- When the accompaniment is playing a C chord, you're safe holding out notes on C, E, or G.

- When the accompaniment is playing an F chord, you're safe holding out notes on F, A, or C.

- When the accomopaniment is playingi a G chord, you're safe holding out notes on G, B, or D.

- If the song goes to some other chord, just play a note or notes that sound right with that chord - this may take some experimentation.

- Between the notes you're holding out, you can play any note in the C scale, as long as you don't hold it too long. Best cases, these are "passing tones" between one note in the chord and another note in the chord.

- If you hit a note that doesn't sound right with the chord, do it proudly, so folks will think you meant to do that, then quickly slide to a note that DOES fit.

- If you're playing jazz, bluegrass, rock, blues, or traditional gospel, you can flat some notes once in a while and get away with it.

- If you're playing modern jazz, you can play in a different mode or even a whole different scale and get away with it as long as it sounds like you know what you're doing (check out Coltrane's solos as an example).

- To train your ear in this sort of thing, listen to folks whose ad libs are melodic, like Stephen Stills, Eric Clapton, Louis Armstrong, B.B. King, and most slow jazz players. Listen to how the melody tracks the chords, and how passing tones tie it all together. Listen to exceptions to major (Ionian) and minor (Aeolian) scales and try to figure out why the exceptions work or if they just sound like wrong notes.

- When you're listening to music - any kind of music, try making up melodies in your head that fit the chords you're hearing. BEST case is if you can make up melodies that "fill in the gaps" around the melody that the singer is singing. If you listen to enough music, you'll realize that this is exactly what the best lead guitar players in many bands often do.

If you're not careful, you must might become a musician, or - worse yet - a songwriter.

Conclusion

We used the key of C for the exercises on this page to make them easy and to show all the different kinds of scales you can play in a single key signature (no sharps or flats). If wanted to do the same exercise in the key, say, of G, just start with a G scale and remember to sharpen the F every time you hit it.

You won't remember all of this the first time you read it. But as you go back through and play the various scales, you'll get a stronger idea of why certain kinds of melodic movement work and why some don't. Hopefully you'll also get some ideas for things you can use in your own songs. And hopefully our discussion of chords will make more sense when you're ready to move on.

Pop Quiz

For a little fun, write the answers to these questions on a piece of scrap paper.

- What major (Ionian) and natural minor (Aeolian) scales can be played on a piano without touching the black keys?

- What "flat" note is played on the same black key as D#?

- What kind of scale has different notes going up than it has coming down?

- How many notes are in a chromatic scale?

- How many notes are in a major scale?

- How many notes are in a natural minor scale?

- What do you call the scale that can be played completely on the black keys of a piano?

- In the key of A minor, which note is most likely to be sharpened?

- C major and A minor

- Eb

- melodic minor

- 12

- 7

- 7

- Pentatonic

- G

All material, illustrations, and content of this web site is copyrighted © 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014 by Paul D. Race. All rights reserved.

For questions, comments, suggestions, trouble reports, etc. about this page or its contents, please contact us.

| Visit related pages and affiliated sites: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|