Evaluating Used Saxophones

by Paul D. Race

Let’s assume that you’ve decided what kind of saxophone you want to buy. If it’s for a kid starting band, it’s an Eb Alto or a Bb Tenor. (If you’re looking for a used C Melody, check out our article Shopping for C Melody Saxes.) If you already have some saxophone “chops” and want to spread your wings a little, you might be looking for a vintage horn. If so, check out our article on Evaluating Vintage Saxophones. This article is for folks wanting a “modern” saxophone, especially to start out on.

The modern era of saxophones started when Yamaha forced Selmer to redesign the Bundy in the mid-1970s (more below). Most horns made since about 1975 look a lot alike, so a 1980 name-brand student horn that has suffered little wear-and-tear and has been looked over by a qualified technician will look and play about the same as the name-brand student horns being made today. One advantage to the sax shopper is that you have a lot of choices, and a lot of those thirty-year old horns cost a lot less initially, so the owner may be willing to part with a horn for way less than someone who just bought an identical horn last year.

The average student horn is an Eb Alto (or Bb Tenor) that has been played for three or four years, then left in the closet until someone decided they need the cash more than they need a reminder of something they didn’t follow through on. Best case - for you - would be that you get it from the original family. They may remember the thing costing $600 back in 1979, and may think charging you $275 is fair. Or they may remember the thing costing $900 in the 1990s and think charging you $450 is fair. By the way, both prices are fair if the horn isn’t going to require serious work to make playable.

On the other hand you might find yourself dealing with someone who found the horn in the above paragraph, cleaned it up, replaced a bad pad or two, vacuumed out the case and listed it as “like new” for $800, knowing that the current equivalent is $1400. Now, a true “like new” horn for 2/3 the new price is still a good deal, but a well-used horn that has been prettied up and falsely advertised is not.

Here’s the fun part: as often as not, the reseller will pretend to be the original owner and swear that it’s always been taken care of. The vast majority of folks selling saxophones on eBay are resellers, and there’s almost no way to tell if they’re being honest with you or not. I’ve seen horns there deliberately mislabeled as to brand, as to age, and even as to kind of horn.

This is where having a real sax player on your side is critical. And learning to tell the truth from urban legends and wishful thinking when you scan the Internet looking for more information about a “too-good-to-be-true” deal.

Note: The advice on this page also depends on you having access to an honest woodwind repair person. Technically almost every woodwind repair person I’ve ever met has been honest. But the stores they work for aren’t always honest. For example, the biggest music store in my area won’t let you talk directly to their repair people. Instead, they’ll try to talk you into a new horn, and if they can’t do that, they’ll charge you double for the repair just because by now you’re a “captive audience.” Ask your woodwind-playing friends who they use - the name of the repair person, not just the name of the store. Often mom-and-pop stores run by instrument repair people will be the most helpful and honest.

Brands and Country of Manufacture

When I said that the vast majority of saxophones made in the USA, Europe, or Japan could still be made playable, you may have noticed that I left out China. Don’t be fooled by thinking that the $250-$350 “professional, instructor-approved” new Chinese horn you see on eBay or Amazon will serve your student as well as a good used model. The list of brands to avoid grows every day, so I won’t bother listing them. But if a deal seems too good to be true, it is. As one example of the difference, there may be far less copper in the “brass,” giving you a horn that has many brittle parts. In some reported cases, the horns played fine out of the box but began literally falling apart within a matter of weeks.

That said, a few legitimate brands have set up factories in China, using quality components and pretty-good quality control. So you may come across a slightly used brand name horn that is still worth considering in spite of the “made in China” stamp.

Post-1979 brand names worth considering for beginning students include:

- Anything from Selmer that is not an original Bundy. Those were great horns for their day and I wouldn’t hesitate to pick up a Bundy Sax in good shape for my own use as a backup horn. But the Bundy II is easier for beginners to play, and all Selmer student horns since have kept the upgraded features.

Since I wrote this article, I had the chance to play an early 1980s Bundy II tenor sax that had most of the finish corroded off but which had been tweaked by a decent technician about a year ago. With my Selmer C* mouthpiece, it had a loud, even tone and pretty good intonation. Except for the looks - which would have embarrassed a beginner, I’d recommend it over any student horn that’s been made in China. Even with the corrosion, it would work for, say, an alto player who needed to double on tenor once in a while. In fact, it would have held its own in 90% of the gigs I used to play back when I was playing “out” regularly.

By the way, the earlier Bundies were actually good beginner horns - they were the Selmer versions of the Buescher Elkhart I learned on back in the early 1960s. The key arrangement is just a little harder for little fingers to reach.

- Anything post-1976 from Yamaha

- Japanese-made Vito (most of them were made by Yamaha). I’ve seen some Taiwanese-made Vitos, but I haven’t had my hands on one. As far as I can tell from photos and reviews, quality is about the same.

- Keilworth, whose student-line horns are now made in Taiwan. Some of them are made by the same people who make Jupiter horns. These vary in quality, though, so bring a sax player along when you go to look at the thing.

- Jupiter is made by KHS, a Taiwanese company that has been making band instruments for decades. Nowadays their student-line saxes are made completely in China, and quality control has been uneven. Still, there seems to be gradual improvement. I would say that a used student Jupiter less than, say, seven years old would be worth considering, all other things being equal.

- Cannonball student saxes have a decent reputation, too. Their better horns have an excellent reputation.

In addition, a “new” saxophone company seems to spring up every few months. Most of these are simply importers of cheaply made Chinese horns. Some of them have a more direct relationship with the suppliers and demand better quality - then they test the horns for playability before they ship them out. I wouldn’t trust either source without getting my hands on the horn first.

Note: If you’re interested in a vintage pro horn, or if you come across one and wonder if it’s a better deal than the student horns you’re looking at, there are some good recommendations and “gotchas” on the Saxophone.org Saxophone Buyer’s Guide page.

The Hunt

If you live in a metropolitan area, Craig’s List may give you a line on several horns. Don’t assume that:

- Any of the information in the ad is correct,

- Any of the sellers are honest, or

- Any of the prices listed represent the true value of the horn.

Pay the most attention to ads with good photos and specific information. Call people who have phone numbers, e-mail or text those who don’t and ask for their numbers and a good time to call. When you’re on the phone, ask about the horn’s history. Generally, you’re looking for a person who started out on the horn and gave it up at some point in high school. If they gave it up after high school, that might mean it went through marching band, which is brutal on horns, but may not disqualify the thing. If the person on the phone is vague about the horn’s history or his story changes, you’re probably dealing with a reseller - he picked this up at a flea market, auction, garage sale, or Craig’s List transaction for a song and wants to make some profit on it. There’s nothing wrong with that, per se, especially if he is a saxophone player and knows what he has. But if he’s lying to you about that, he’s probably lying to you about other things. (I have bought saxes from people I knew were lying to me, but I know enough about the things to draw my own conclusions.)

Keep in mind that even the best-case horn will require a trip to the repair shop for tweaking before it’s ready for your student, so you might want to mentally add at least $100 to the cost of the horn you’re looking at when you’re balancing pros and cons.

If you’re tempted by an online ad, look for one with lots and lots and lots of in-focus photos. If this guy seems like a reseller (most eBay sellers are), look at the seller’s other stuff and see if he seems to sell a lot of saxophones - if it’s a bass guitar player who picked up a sax in trade, he may be innocently ignorant of problems with the horn or cluelessly passing on fake history information that he was given. Also, a 100% positive feedback rating from a fellow who usually sells Hummel statues may not indicate that this guy is really ready to give you the information you need to make the right decision. Based on what I said about even the best horns needing a trip to the repair shop before they’re student-ready, you might consider mentally adding at least $200 to the cost of any horn you’re looking at on the internet.

Looking It Over

Let’s assume that you’ve used Craig’s List and found a local horn or three that might suit your needs. Or you have a heavily-photographed, believably documented, reasonably priced possibility on eBay. Here are some things to look for:

Obvious Damage

Now I’ll be honest, a saxophone can be pretty banged up and still play well. But signs of careless handling or apparent abuse might indicated hidden problems as well.

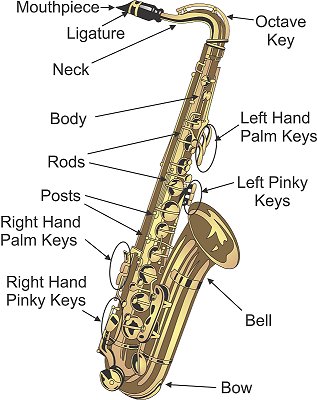

The bell is the part that most folks think the sound comes out of. It’s shaped like the opening of a cornucopia. If the bell is bent out of shape in any way, you should probably write the horn off period. Yes, it can be fixed, for a price, but it is almost impossible to damage the bell of a saxophone with normal handling. The horn has been dropped and possibly abused.

The bow is the U-shaped part that connects the bell to the body. The most common ding on saxophones is a dent from banging the bow into something (or maybe dropping the horn on the bow). Professional horns have a guard that protects the bow. Student horns generally have some reinforcement which may not quite do the job. But a slightly dinged bow is so common that a lot of folks wouldn’t even notice the difference in sound. I’d say if the ding is less than the size of a 50-cent piece and no deeper than, say 1/8”, and the brass is not punched through or significantly creased, I wouldn’t worry about it too much. If there are a lot of dings on the bow, it may have been a school-owned horn and been abused in other ways. If any of the dings looks like it would alter the flow of air through the tube (say it’s very broad or deep or both), assume that the horn has been dropped hard enough to distort the body and knock things out of alignment.

Up at the other end, the neck is the part that connects the mouthpiece to the body of the horn. It will have a loop-shaped lever with a pad on one end - that’s the octave key. The cork on the neck should not have big holes - this is an inexpensive fix but indicates that other things might need fixed as well. A few scratches on the neck don’t hurt anything unless you promised your kid a new-looking horn. But if the pad on the octave key doesn’t sit squarely over the tone hole so that it has a optimum seal, and you can’t make it fit squarely over the tone hole by adjusting it with a little pressure, something’s wrong. A bigger problem is if you see any sign that the the neck has ever been bent at all, such as bulging or cracks in the lacquer. Run - do not walk - away. Also look for signs that the part that goes down into the saxophone has ever been resoldered to the neck - that may be a sign of an innocent accident or a symptom of a pattern of abuse.

The keys are levers that make the pads open or shut on the horn. About eight of them have mother-of-pearl-ish buttons (called “pearls”) that are glued right to the metal over the pad. The rest are connected to the pads by long levers and sometimes by a series of rods and levers. Look the horn over and make certain nothing seems to be missing. Everywhere there is a post (the chess-pawn shaped supports), there should be something attached to it, a key or a rod or something. A “freestanding” post means that the horn is missing something that will cost real money to replace. Operate each key, even if you don’t know which fingers go where. The motion should be smooth and precise, not sloppy or sluggish.

By the way, if a pearl or two are missing, that’s an inexpensive fix, but it might indicate a pattern of abuse.

Wear patterns on the keys that are not buttons do not disqualify the horn. For example, there are several lever-shaped keys that are arranged to so a player can hit them with the palm of his or her hand. At least one of the palm keys in each cluster will show significant wear if the horn’s been played at all.

Below the normal right and left hand position are other keys that the player is supposed to hit with his pinky. Again, at least one or two of the pinky keys in each set will show significant wear if the horn’s been played at all.

Incidentally the shape of the right pinky keys will show you if you’re looking at a ”modern” horn or not. In the mid-1970s, companies started applying what Selmer Paris engineers had learned about ergonomic key locations to student horns. One obvious update is that the right pinky keys are now tilted for easier playing. A far more obvious difference is that the lowest pads (for B and Bb) have been moved to the right side of the bell, from the player’s perspective. Incidentally the shape of the right pinky keys will show you if you’re looking at a ”modern” horn or not. In the mid-1970s, companies started applying what Selmer Paris engineers had learned about ergonomic key locations to student horns. One obvious update is that the right pinky keys are now tilted for easier playing. A far more obvious difference is that the lowest pads (for B and Bb) have been moved to the right side of the bell, from the player’s perspective.

Don’t get me wrong - I cut my teeth on the older-style horns, and many of these, like the Beuscher Aristocrat and 400, and the first-generation Selmer Signet are better than any student horn in equivalent condition.

But if the seller’s telling you that a horn with pre-1975 key configuration is only ten years old, he’ll lie about other things, too.

Again, noticeable wear on one or two of the pinky or palm keys in each cluster just shows an average amount of wear for a horn that was played 3-5 years. If there’s noticeable wear on all the palm or pinky keys, you’re looking at a horn that has been played much longer. As long as it’s been taken care of, that’s not a problem. But if the seller is telling you his sister bought it new, played it for one year and locked it away, he’s not telling you the whole story

The posts are the pieces that support the keys and the rods. They are shaped like tiny stanchions or chess-piece pawns. Look at the posts, especially those that are most exposed, for signs that:

- The post has been broken off and resoldered back on.

- The post has been bent

- The post has been knocked askew in such a way that has bent the body of the horn underneath it.

All three cases could be a sign of abuse, especially if the horn has other problems. However, the first case could be a symptom of an isolated accident. If the resoldering job looks professional, chances are it was done by a repair person who made certain everything was fixed when he or she did the work. The second case probably indicates that the horn needs real work. The third case may mean that the horn is irreparable. In any case, damage to any post drops the resale value of the horn considerably, and makes a lie out of any “like new” claim.

The rods are the long tube-looking things that connect some of the key to pads that are several inches away. There should be no noticeable wear on the rods unless the horn was constantly mishandled. Sight down the horn like you would an arrow. If the longer, more exposed rods bow in a little that means that the horn has been carried the wrong way, but that doesn’t make the horn a write-off in and of itself, especially if the keys and pads attached to the rod still seem to be doing their jobs smoothly and precisely. The one rod problem that disqualifies a horn automatically is any sign that a rod or rods have been knocked out of shape and “re-straightened,” or that a whole assembly has been knocked askew.

Under many of the rods are springs, little steel rods or pins that hold the pads in their default position when you’re not playing the key. If you push one of the lever- or rod-attached keys and nothing happens, it could be because a spring is broken off or missing altogether. Again, this is a minor repair, but if the seller swears he was playing the thing just yesterday, don’t believe anything else he says either. By the way, accomplished sax players all know how to temporarily “fix” missing springs by wrapping rubber bands around the horns. Don’t laugh - rubber bands have gotten a lot of pros through the rest of their gig but they shouldn’t be left on once the gig is over. If you see an unusual corrosion pattern running across the rods or the body, that may indicate that someone “fixed” a missing spring with a rubber band and left it on for months - another sign of neglect that often appears on former school horns.

In one end of each rod is a set screw. If any of these are missing, the rods don’t stay on the horn, so chances are they’re all there, unless you notice that a screw has come out and been replaced by a sucker stick or something.

The pads are the little leather disks that seal off the holes of the horn. If the pads are white, you’re almost certainly looking at a vintage piece that will require a repad and probably other work, but you probably knew that. If the pads are a natural leather color, feel them and see if they seem soft and resilient. A 40-year old horn that has been stored properly will still have soft pads, except for the top few. Chances are the pads nearest the top of the horn will be dark and hardened, perhaps even cracked. That’s because moisture from playing affects those pads more than the others. If no more than three pads have started to harden, this is normal wear, and will be covered by the $100 buffer I told you to mentally add into the price of the horn. Open and close every pad on the horn. If many of the pads are sticky, that means the player drank a lot of Coke while playing the horn, and it might need a good cleaning. Each pad should fit firmly over the tone hole in exactly the circular pattern that you can see indented in the pad. That indent was put there when the horn was assembled. If many of the pads don’t sit firmly on the indent, or have two circular indents, those keys have been knocked out of alignment, which could be a sign of bigger problems.

The Finish - Most finish issues are cosmetic. If there are a lot of scratches, though, you may be looking at a school horn, which means that it has been abused. If the metal under the scratches is turning green, there may be more wrong with the horn than you will want to deal with.

On the other hand, if the finish is “too good to believe,” especially on an older horn, it may have been relacquered at some point in the past. I recently saw a 1920s-era sax being sold as a 1980s horn because the lacquer looked good. Unfortunately that model was only ever sold in a silverplate finish. Relacquering a student horn isn’t necessarily a bad thing - it must may mean that appearance was important to the owner at some point in the horn’s history. But if the seller is lying or ignorant about that, he may be lying or ignorant about something else important as well.

If you’re uncertain whether a horn is relacquered, and it will affect your purchasing decision, check out “Dr. Rick’s” Relacquered Saxophone Page.

Summary of What to Look For

Once again without all of the explanation, here’s a list of thing you should and shouldn’t expect when evaluating student horns.

To summarize, here are signs of normal wear for a horn that was played 3-5 years:

- Light scratches on the neck, on the bow, on the back of the body, and especially around the hook where the strap attaches.

- Light wear-through of the finish on one or two pinky keys and palm keys in each cluster

- Minor dings in the bow

- Some hardening of the top three or four pads

Here are signs of heavy wear - these don’t disqualify a good horn that has otherwise been taken care of, but if your student is worried about the cosmetic appearance of the horn, that might be a problem:

- Neck cork could stand replacement.

- Top three or four pads are quite hard, several more are starting to harden. (This will raise the cost of refurbishment, but might be worth it for an otherwise good horn.)

- Heavy scratches on the neck, bow, and body. Lacquer possibly gone in patches.

- Finish wear-through on most of the pinky and palm keys

- Lots of dings on the bow

Finally here are signs that could indicate abuse, dropping, and/or improper storage (such as a hot attic). Only a few will disqualify a horn by themselves, but more than a couple of these on the same horn means that it was seriously mishandled and may have problems you can’t see.

- Most of the pads are starting to harden (you may be looking at a partial or full repad, which won’t be cheap)

- The bell is bent out of shape (I’d skip a student horn just on this account).

- Many dings on the bow including some that are deeper than 1/4”.

- Several missing pearls

- Rods have been bent out of shape (even if they’ve been bent back)

- Posts that have been knocked off and resoldered or that have been bent (especially if they distorted the body shape)

- Any sign that the neck has been bent.

- Horizontal stripes of discoloration or corrosion on the rods - evidence of rubber bands left too long on a horn after a spring failure.

- Evidence of resoldering anywhere on the horn.

Again, these issues wouldn’t dissuade anyone who was shopping for a pro or classic horn. But so many student horns are available in most markets, you’re better off moving onto the next deal. Even a “free” saxophone with two or more of the problems listed above will probably cost you more to get fixed up and take care of than it will ever be worth.

Other Resources

Saxophone.org’s Saxophone Buyer’s Guide page has some good tips, especially if you’re looking for a pro or classic horn.

Other articles you may find helpful include:

Another resource, the Horns in My Life articles describe various saxophones (and one flute) with which I’ve made a personal connection over the last 45 years. Some folks who’ve had similar horns will find it a helpful resource. Others will just like to reminisce along with me. On the other hand, if you come across one of these horns while you’re shopping for a saxophone and want to know more about it, you may find one or more of the articles helpful.

The list is in the sequence in which I owned the following horns, not in the sequence they were built, which is way different.

All material, illustrations, and content of this web site are copyrighted © 2011-2015 by Paul D. Race. All rights reserved.

For questions, comments, suggestions, trouble reports, etc. about this web page or its content, please contact us.

| Visit related pages and affiliated sites: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|